In 2015, artist Thomas Lommée wrote “The next big thing will be a lot of small things” on the façade of the university in Ghent. The time of the large-scale project, the "created" city no longer exists and cannot exist in a landscape that is completely built up. "The Netherlands is completed," our neighbours would say. The time of transformation (in Dutch: ver-bouwen) is fast approaching. This requires new projects and new coalitions. Just because they're small in the light of the emerging changes, they won’t necessarily have less impact. Together they add up to a bigger picture that we can never conjure on our own. That is why new platforms are also needed that focus on bundling and connecting disseminated knowledge and initiatives.

We analyse these shifts in the Eurodelta's operational zone: the delta region of the Rhine, Meuse and Scheldt rivers, which is historically very fertile and therefore inhabited intensively, and which largely overlaps with the cultural boundaries of the Low Countries (Architecture Workroom Brussels et al., 2017). Our land use, production and housing model cannot be defined according to national or regional boundaries and must instead be viewed and planned according to a shared territory. The two administrative regions of the Netherlands and Flanders, which share the same delta subsurface and a strongly intertwined economy, look at each other with increasing interest. As a non-profit organisation, Architecture Workroom (AW) has deliberately focused on the Delta as a coherent spatial field for the last decade. Based on this, in the following article we present a reading of the changing architecture and planning practice in Brussels, Flanders and the Netherlands, against the background of the contemporary time frame and the tasks that go with it.

In which context should we position the contemporary spatial practice? Politically, we look at an increasingly wider gap between ideologies. In 'Down to earth', Bruno Latour succeeds in rationalizing this spread position by examining what we can learn from the prevailing climate negationism (Latour, B., 2018). He dissects Trump's withdrawal from the Paris climate accords as a reaction to the feeling that unlimited growth simply does not fit into the available territory. The only answer - if we are not willing to adjust our thoughts on growth - is to then firmly deny that territory. But what can we do to counter this "bottomless" thinking? Latour leads us back towards Earth. This movement is based on the observation that, in our current time frame, everything starts as an ecological issue. It is not about choosing between the social or ecological side of the story, we will only be able to tackle our social challenges if we do so from the source of our existence: our soil, our territory, our Earth. And we don't have to romanticise about this: that soil doesn’t look like it did a few hundred years ago, (the influences of) humans have become inherently part of the system. To use the most obvious and literal example: we can create charts of the composition of the subsoil as it looked about a hundred years ago. But we have no idea of the most current soil conditions. Why? Because it cannot be logically extrapolated according to scientific principles, and has been influenced and mutated by irregular and difficult to trace human interventions. The atlas of the current state of our territory, which we actually need to make informed decisions, doesn't yet (or rather: no longer) exist. Or if we interpret Latour a little more broadly: it is in space, in the tangible reality where everything comes together, where we can work on change. Technological innovations can help us with this, but when it boils down to it, the spatial sum total must always fit.

We find ourselves in a region that has gradually been built up, but where unimaginable changes demand more and more space. We are facing a Great Transformation. The transition from fossil to renewable energy will be felt right into the capillaries of our living environment. More and more severe weather conditions - certainly in a delta such as ours - will not only be met on the coastline, but will require measures that penetrate deep into our cities. Our food production, currently very intensive and highly technological, must be brought into line with a healthy ecosystem and with our growing urbanization. And although the major goals that we have concluded together seem far away, transition is not new. About 150 years ago, the industrial revolution triggered such a dramatic change that most of the norms and values as we know them today are marked by that moment (Polanyi, K., 1944). Not everything had a price prior to the industrial revolution. The idea of poverty is relatively new, dating back to only 1750, as with the idea of unemployment. And the moment land became a market commodity, we became dependent on market logics for our drinking water, food and living. Our territory as we know it this very day is divided into sectorial zones where agriculture, water or biodiversity should compete with real estate industries. Relying on Latour we could argue that this is actually the place of integration, where market logics should no longer play a dominant role. A plea for the de- and revaluation of land.

While initially governments aimed to temper unwanted social effects of the market economy through social protection, and unwanted spatial effects through a growing planning culture, a great deal of that social and spatial framework has now been passed on to private players (the socialization of healthcare, as well as the construction of sewers and heating networks by private investors, or the construction of large bridges and buildings by wealthy entrepreneurs in DBFM models). The increasing pressure on our urban landscapes and the "battle for space" is now forcing governments to take responsibility (again) and to steer it towards conscious choices. They can no longer be a neutral facilitator nor allow markets to define through price setting what is important and what isn’t (Mazzucato, M., 2018). If we believe for example that sustainable local food systems are crucial, access to fertile land will have to be organized and safeguarded publicly. Such a food strategy cannot be developed without the farmers, citizens' initiatives, civil society organizations, academics and public figures that form local coalitions and take up responsibility and ownership in concrete projects. It is the combination of a stronger centralized public framework on the one hand that allows for a stronger decentralized field of action and multiplication on the other hand. There exists a striking cultural difference here between the Netherlands and Flanders. For the traditional top-down Dutch policy - developed to make a sub-sea country safe and habitable - the idea of a decentralized organization of small-scale projects goes against all existing instruments. Flanders has never known the same central movement and will have to look from the bottom up for logic and coherence to steer different projects together in the right direction, in a coordinated way. But we see, on both sides of the border, that a new balance is being sought.

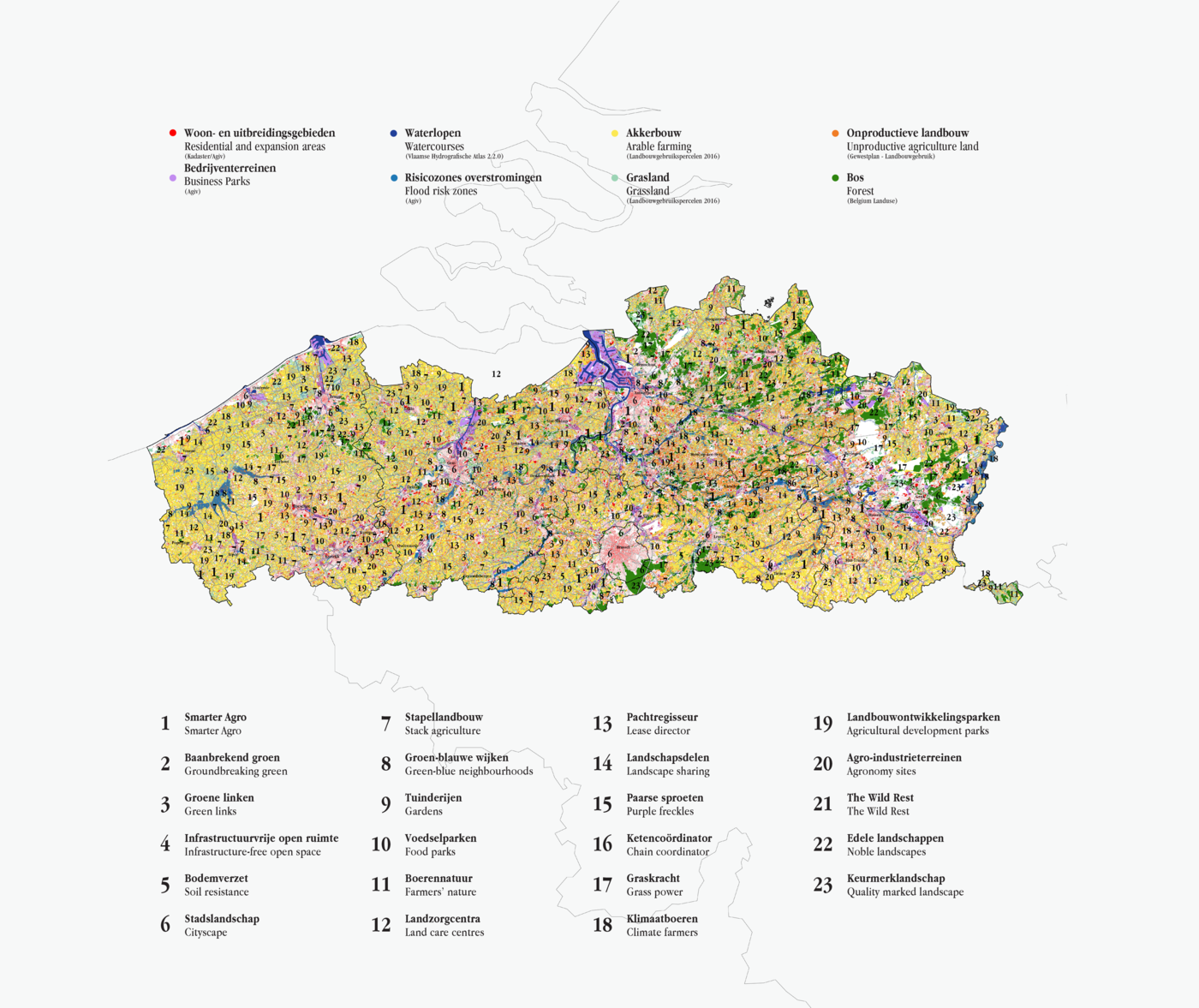

To fit The Great Transformation into our available territory, we need new approaches with new instruments (or better: new interpretations of existing instruments). Together with and thanks to many partners, AW gradually developed a "programmatic approach" that allows national and regional goals to be achieved at local level in new coalitions (Declerck, J., 2018). We place a third method between generic and area-specific policy: by stacking different map layers on top of each other, we recognize promising combinations that we classify into "families of challenges". The projects and strategies for those similar places can be designed together. Instead of the large regional project we aim for smaller, manageable and common projects that can be realized in a new implementation mode between government and local coalitions.

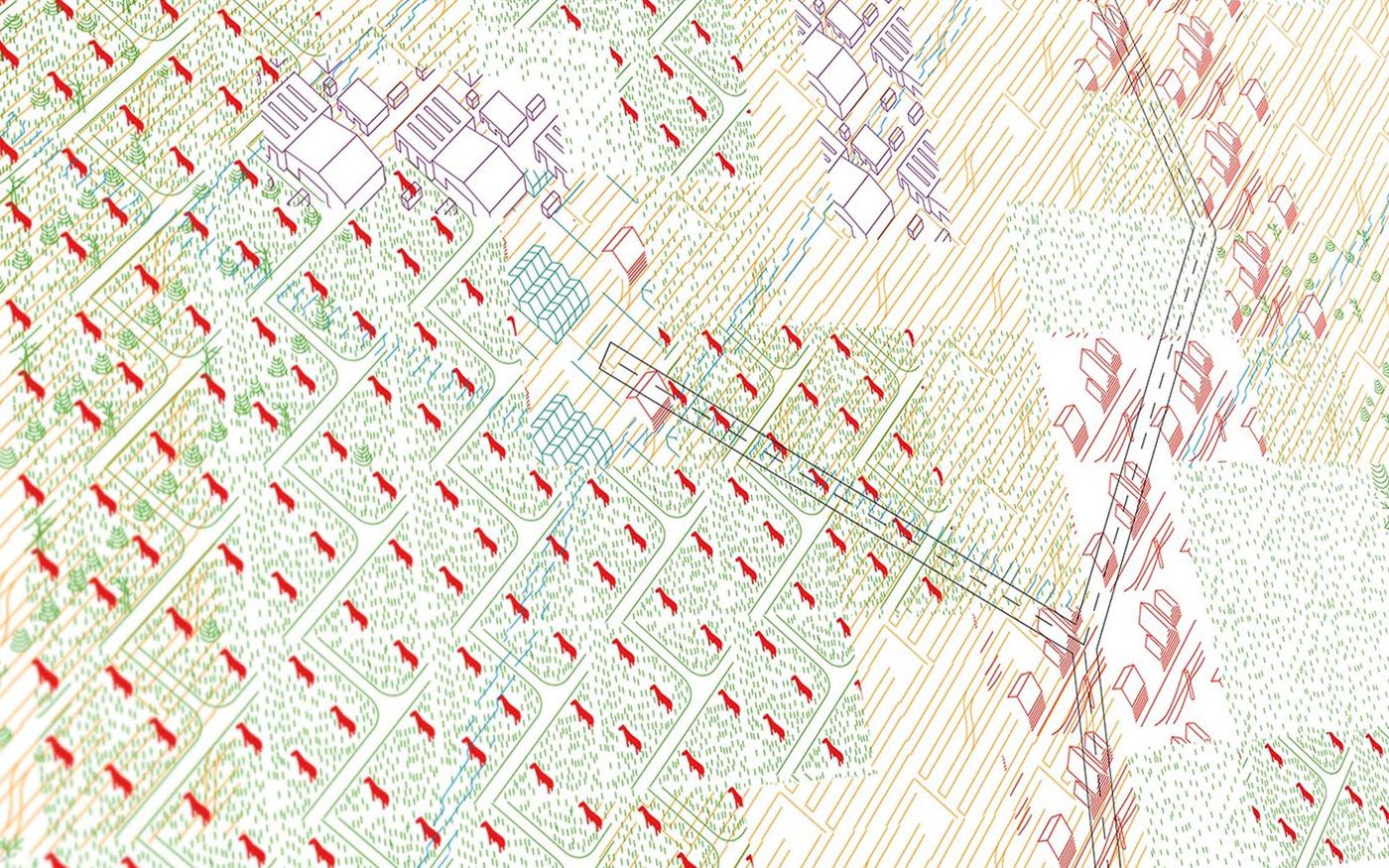

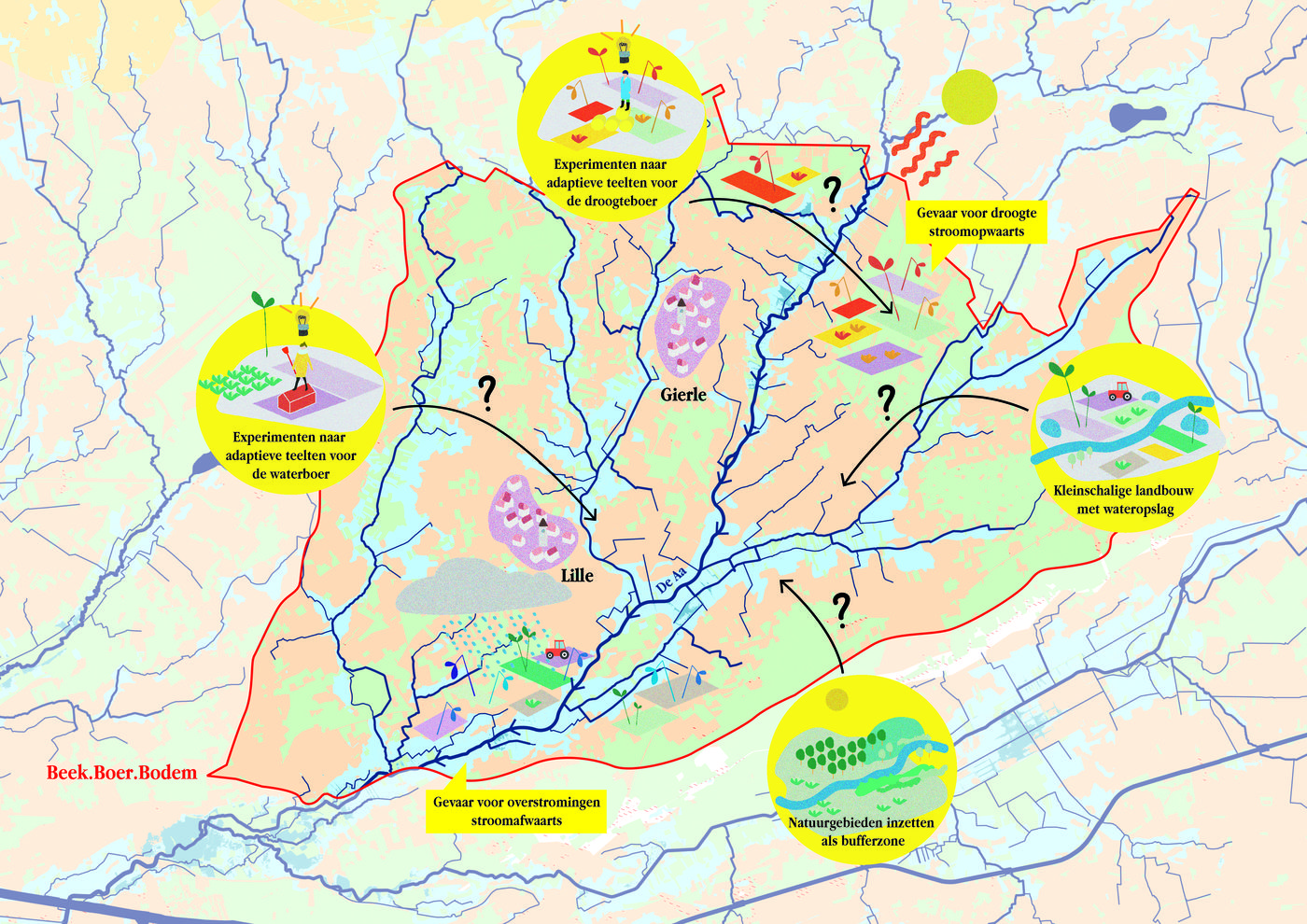

The principle of accumulated map layers was worked out for the first time in "The Ambition of the Territory", a study by the coalition AWJGGRAUaDVVTAT that filled the Belgian pavilion at the Architecture Biennale in Venice in 2012. The cartography that was developed for this purpose, outlined an alternative to the traditional zoning plans that try to delineate different forms of use and the interest groups associated with them sectorally. One plot, one function, one colour. The complexity of our territory was represented in this new cartography instead by a superposition of different overlapping map layers, which made the interactions and conflicts between different users and activities legible. The next step in this discourse was made in Atelier BrabantStad in 2014: the translation of regional cartography into integrated sub-projects or “machines”. The Noord-Brabant region with its colourful mosaic of urban areas, intensive agriculture, avenues, villages, industrial activities, river valleys, nature reserves and canals should be viewed as an urban carpet. The result of the research was a multi-coloured regional mapping, symbolically executed for the occasion on a twelve by three meter large tapestry. This map worked as a foundation for six “machines”: combinations of tasks, with real actors and concrete situations, that are recognizable at different places in the region and that integrate challenges and opportunities related to quality of living, water management and innovative entrepreneurship. For example, by redeveloping outdated industrial areas around collective water storage and purification systems, we combat heat stress in residential areas and we create a healthy urban environment for new economies, where purified water can be used against desiccation, in the canal system or for industrial purposes. This is how problem situations become opportunities. A third project then demonstrates how this approach leads to a structural multiplication of implementation in the field. The Open Space Movement bundles the objectives of different policy domains and depicts them spatially, showing where cooperation is possible. Via a call, local coalitions can be found that are already engaged in linking these goals on the ground. For example, a first program "Water-Land-Schap" was launched in 2017. The Minister of Environment, Nature and Agriculture set aside five million Euro for the joint support of fourteen comparable projects. The government doesn't just grant a subsidy, but it learns to collaborate better between policy branches and with various stakeholders in society. And although not all submitted proposals can be honoured and supported individually, they remain involved in a learning environment, so that not just 14, but 40 initiatives can surf along with the government investment.

In these programs, manageable projects are defined which add up to a comprehensive transformation strategy. But those will need new practices and new coalitions to facilitate and execute them. It is imperative that the role of the (urban) designer broadens (again): beyond the plan on paper, towards a permanent involvement in the daily reality of legal and financial obstacles, precisely to better understand how to design. We see design agencies that are increasingly taking on the role of intermediaries in cooperative development projects. They act as mediators, legal and financial experts at the same time (for example, Miss Miyagi in Belgium or the VvE’s with energy in the Netherlands). We see that architects set up constructions in which they are material producers, designers and contractors so that they can rotate circular materials much more frequently (for example, Rotor or BC architects). We see new collaborations between designers, local authorities, citizens, organizations and universities in order to include social dimensions in conjunction with planned investments in urban development and management (for example, Endeavour, Stiemerbeekvallei or Mozaïek Dommelvallei). We see that "making city" goes hand in hand with new mechanisms such as rolling funds, neighbourhood non-profit organizations or cooperatives and hacks of existing subsidy or investment flows. Together with the Kopgroep Stedelijk Beheer (“Urban Management Group”), for example, AW is now investigating how a social "by-catch" can be generated when repairing or replacing the sewer system. Summed up, 15 billion Euros are spent annually in the Netherlands for managing the public space. These astronomical budgets can simultaneously realize the social, sustainability and circularity objectives. Only with our boots on the ground, we can shape an alternative regional and even a national approach. But these days, there is a procedural and legal "wall", with formatted structures such as tenders or competitions, between those who ask the questions (and thus define the framework) and those who compete to provide the best possible answer within the given framework. The design practice, which has the power to integrate tasks and translate them to socio-spatial qualities, is thus locked into a culture of single formats and competition. And this is while our challenges are increasingly complex and versatile. From that shared feeling, the Delta Atelier was created in 2018. Fifty practices, supported by the Flemish and Dutch governments, want to reposition the role of the design practice. Here, practices are given room to invest their capacity in knowledge exchange and in co-creatively formulating the most relevant questions or new ‘assignments’.

To bundle new programs and coalitions into an ambitious project for the future, we need to learn from each other at lightning speed. The big question that concerns many experts is how we can scale up much faster and yet qualitatively. Under what conditions - or else: at what price - can we accelerate, grow and multiply? How do we prevent best practices from fading into mediocre consultancy services behind a smokescreen of green promises, of which the most difficult aspects are cut off, resulting in system maintenance instead of a system change? We argue that in order to collectively formulate answers to these questions, we will need two types of platforms: both a broad (digital) network and database ànd the places that bring people and ideas together physically.

Michel Bauwens puts commons and peer-to-peer learning forward as the central levers for social change (Lotens, W., 2013). Peer-to-peer assumes a one-to-one exchange between equals. It does not matter whether you are a department head or technical draftsman; in the p2p model, cooperation takes place in a horizontal manner. Therefore ‘mutualising’ or making knowledge collective is necessary. There have been social practices that innovate together and shared use is not new. But scaling up good ideas has always been a huge barrier. This could change rapidly now that large-scale collaboration reaches a new level via the internet. Do everything that is heavy locally and everything that is light globally, Bauwens argues: he calls that principle cosmo-localism. You produce the materials for a building as close as possible to the construction site, but you can design the concepts and plans together with people from all over the world.

In addition, to facilitate encounter, physical places will always be needed. How do you design those new spaces where horizontal cooperation between citizens, entrepreneurs and organizations, academics, interest groups, policy makers and politicians can work? Pakhuis De Zwijger is a good example, a cultural house in Amsterdam that provides a forum for discussions about a sustainable urban society with a program of debates, presentations, theatre performances and exhibitions in what used to be a cold storage warehouse. A conscious choice was made for a substantive line around the themes of creative industry, city and global trends. And whoever participates in an event - which is almost always free - becomes part of a broad community of “city makers”. A completely different example is De Andere Markt, located in a shop window in one of the village centres around Genk. The physical location close to the residents serves as a base and starting point for the development of a much broader and more widely spread network. Feel free to call it the “social infrastructure” in a neighbourhood where there is freedom to experiment and the goal is to strengthen the local community, to then translate the tasks that are harvested here to an extra-local knowledge and political level. There is a continuing need for such productive settings to explore alternative strategies and methods and to bridge the “missing link” between field initiatives and ambitious paper goals. Between June and December 2018, in the former WTC 1 tower in Brussels' s Noordwijk, we tried to push this idea one step further. We were given an entire floor, no less than 1,500 m2 with an extraordinary view of the city, available in temporary use before the towers would be redeveloped into offices and luxury apartments. Under the cover of a cultural project - an exhibition and program in collaboration with the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam - we designed the twenty-third floor as the ultimate physical in-between space: an inspiring work exhibition with the work-in-progress of Dutch and Belgian practices, work sessions, guided visits, public debates and lectures brought together more than 10,000 actors, ranging from the Flemish government to local and regional policy makers and design practices to farmers working out drought measures with governments. The participating actors experienced this collective workplace as a productive incubator or joint innovation platform: major issues were translated into concrete actions and projects in the field, which are or will be implemented now and in the near future (including the programs Water-Land-Schap, De-hardening and Drought). With an investment of around 1.2 million Euro and with the social expertise and support, new investment programs worth around 20 million Euro could be conceived, launched and supervised. Would these also have arisen without the existence of a physical in-between space? Perhaps, but the fact that they were launched and shown together made them part of a movement that was exceptionally mobilizing.

In the delta, every square meter is now spoken for, to store water, generate energy, produce food or live. How do we reconcile those claims knowing that the population and (therefore) the tasks will only grow? The Great Transformation challenges everyone, but also the spatial practice, to reposition itself in the triangulation between market, public government and civil society. The role of spatial design and planning is to facilitate change to “land” in our shared territory: through new projects, new coalitions and new platforms that embrace complexity. The Great Transformation is a call for reflection, but especially for cooperation. In Flanders and the Netherlands, 2% of the built space is re-built annually. Let's direct this incremental transformation through a multitude of small things, to materialize the next big thing.