Global and local challenges are increasingly manifesting as complex spatial issues: from the energy transition to the socialisation of care and sustainable mobility. This is translating into a renewed belief in the potential of design to help steer our future in the desired direction. Recently, diverse, innovative policy initiatives, projects and exploratory research by design have been launched within LABO RUIMTE - an open cooperation partnership involving the Flemish Master Builder Team and Environment Department - but also in lots of urban projects and biennale ateliers. It’s now time to bundle the resulting knowledge, insights and experience.

The 'Designing the Future' sessions focus on developing a shared agenda for designing a better future. Answers are sought to the following questions: what lessons can be learned? What have we achieved so far? But above all: what are the next steps? How do we implement policy intentions in practice? How and with whom do we embark on this undertaking?

Seven Designing the Future sessions were organised by Architecture Workroom Brussels, the Flemish Master Builder Team, the VRP (Flemish Association for Spatial Planning), OVAM, (Public Waste Agency of Flanders) and the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam.

In April 2018, a corresponding publication was brought out. Designing the Future is a ‘workbook’ on research by design as a lever for social transition. The book does not serve as the finale, but a step towards the development of an alternative work environment.

1. The caring city

Our views on health are constantly changing. Nowadays, health is considered more than ever to be our personal responsibility. At the same time we are observing growing health inequalities emerge, especially in large cities. This raises questions. Is it enough to underline our personal responsibility? Or do other levers exist for working on a healthy city? The link between health and urban development is age-old. In the past, urban development focused for a long time on eradicating disease and injury. Nevertheless, just as our views on health are evolving, the way we view healthy urban development is changing too. The emphasis is shifting from 'cure' to 'care'.

What policy is needed to achieve a healthy and socially inclusive city? How can the authorities act as a choreographer, and organise a more equal (care) playing field, to promote collaboration between capital-rich and fragile actors? And which role could designers play in this objective? During the past few years, research by design and pilot projects both in Belgium and the Netherlands have set out and tested alternative approaches on what a caring environment could offer in the future.

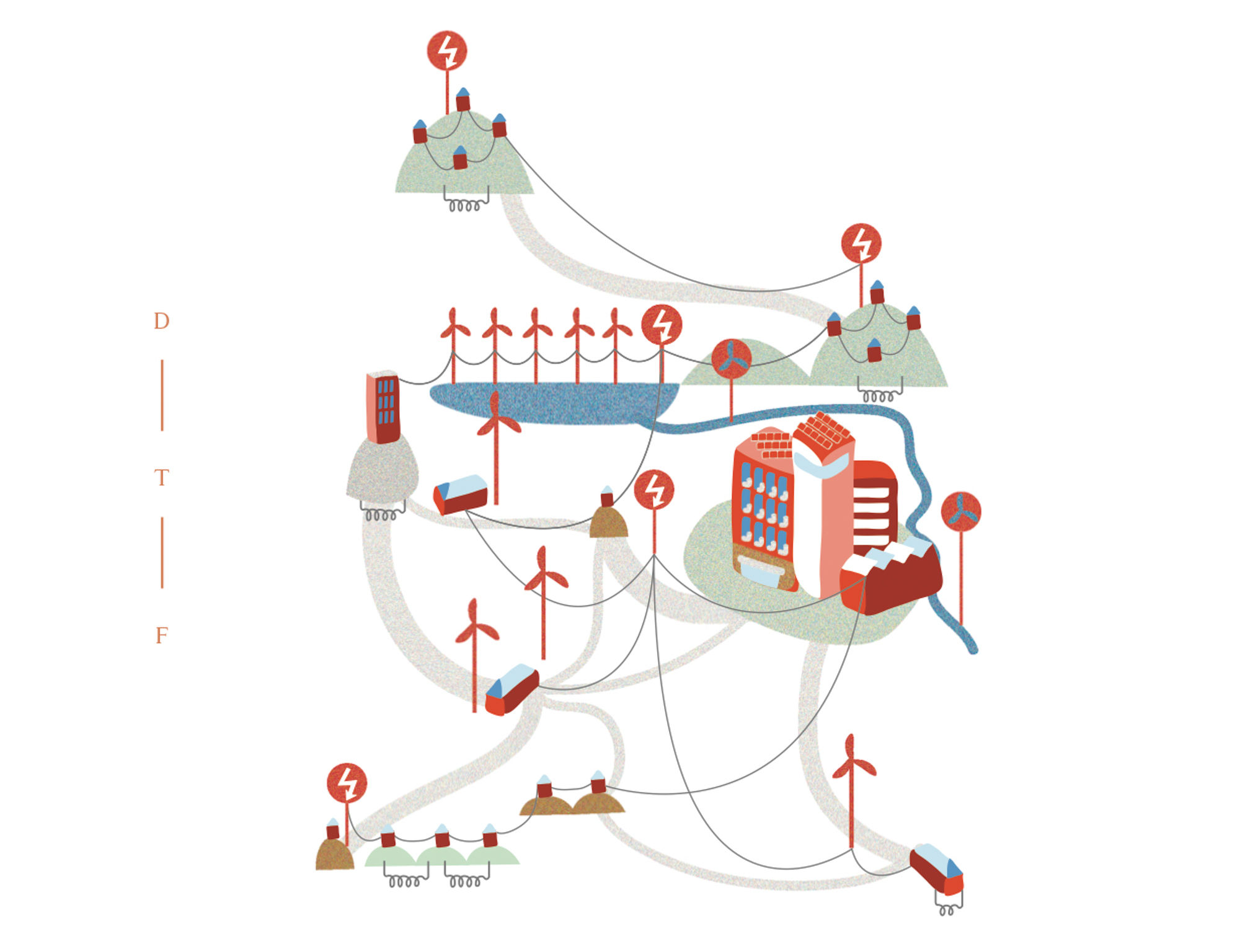

2. Energy landscapes

The fact that it is high time for a radical energy transition is evident, for example, from the climate targets. Actually implementing these ambitious targets in practice is not straightforward. However, considerable progress has been made recently through research by design. Key to this endeavour is the question of how the energy transition could be approached to radically rethink the design of our living environment and the related landscape. How could alternative forms of energy generation be applied in the fragmented landscape that characterises our region in which space is scarce? How could our thinking transcend an individual, separate and sectoral approach? How could the energy issue be linked to social challenges? What other forms of spatial use are conceivable? These are just a few of the many questions on which we want to reflect by bundling and exchanging recently acquired knowledge. We do so in association with diverse parties, businesses, nature organisations, knowledge institutes and government agencies, with the aim of devising specific proposals and actions.

3. The productive city

There is a need for a radically different view on how we make space for work in the city. Because we have prioritised housing and offices over the manufacturing economy for decades, the labour market has been driven from the city to the periphery. If we no longer view the city as an isolated environment, but as part of a much greater economic region and system, many opportunities emerge for shared gains in the long term. This requires an approach that strives for the productive economy to be strategically anchored. The latter necessitates, for example, the manufacturing industry's reintroduction in the city: from manufacturing that provides a link between knowledge, innovation and production, to the circular economy that uses shorter and more sustainable economic chains. The metropolitan region benefits from an economy that focuses on local production and employment, on recycling and short cycles.

How could industry be reintroduced in the city? How could this reorganisation of the city contribute to improved mobility, in terms of commuting as well as transport? Which social gains could be created? In Brussels, as well as other cities, attention for the productive city has increased significantly in recent years. This has manifested in a rich and varied range of projects and initiatives.

4. Visionary housing development

Housing is and always will be a controversial topic when it comes to the future of the city. Urbanisation is increasing: more and more people want affordable and quality housing in the city. Society is also changing: dynamic processes such as immigration, an ageing population, population growth, new family compositions and new living-working situations require changes in how and where we live. In recent years, many refreshing policy initiatives and (pilot) projects have been launched to tackle the urgencies and challenges related to housing in a qualitative manner. For example, there was a greater focus in care housing and collective forms of housing. Many lessons can already be drawn from these projects. At the same time it remains necessary to look to the future and actively seek visionary alternatives that provide solutions to the many challenges related to the housing of the future.

5. Designing with flows

When designing with flows the city forms the starting point as an urban metabolism. By analogy with a living organism, the city is viewed as an ecosystem. The city is no longer considered to be a static, delineated territory, but as a constant flow of goods, capital and people. In recent years, many studies have been conducted in which diverse flows of materials, nutrients, water and other forms of energy that flow in and out of the city, were mapped out in a mathematical or statistical manner. At the same time, metabolism as a concept also forms the rationale for rethinking all kinds of political, ecological, economic and social systems.

On the other hand the practical application and especially the spatial translation of this concept is currently rather limited. Diverse, exciting experiments have been launched in our region with a firm belief in the potential of this approach for more circular, inclusive and resilient cities. It is now a question of further developing the ideas, insights and expertise they have produced.

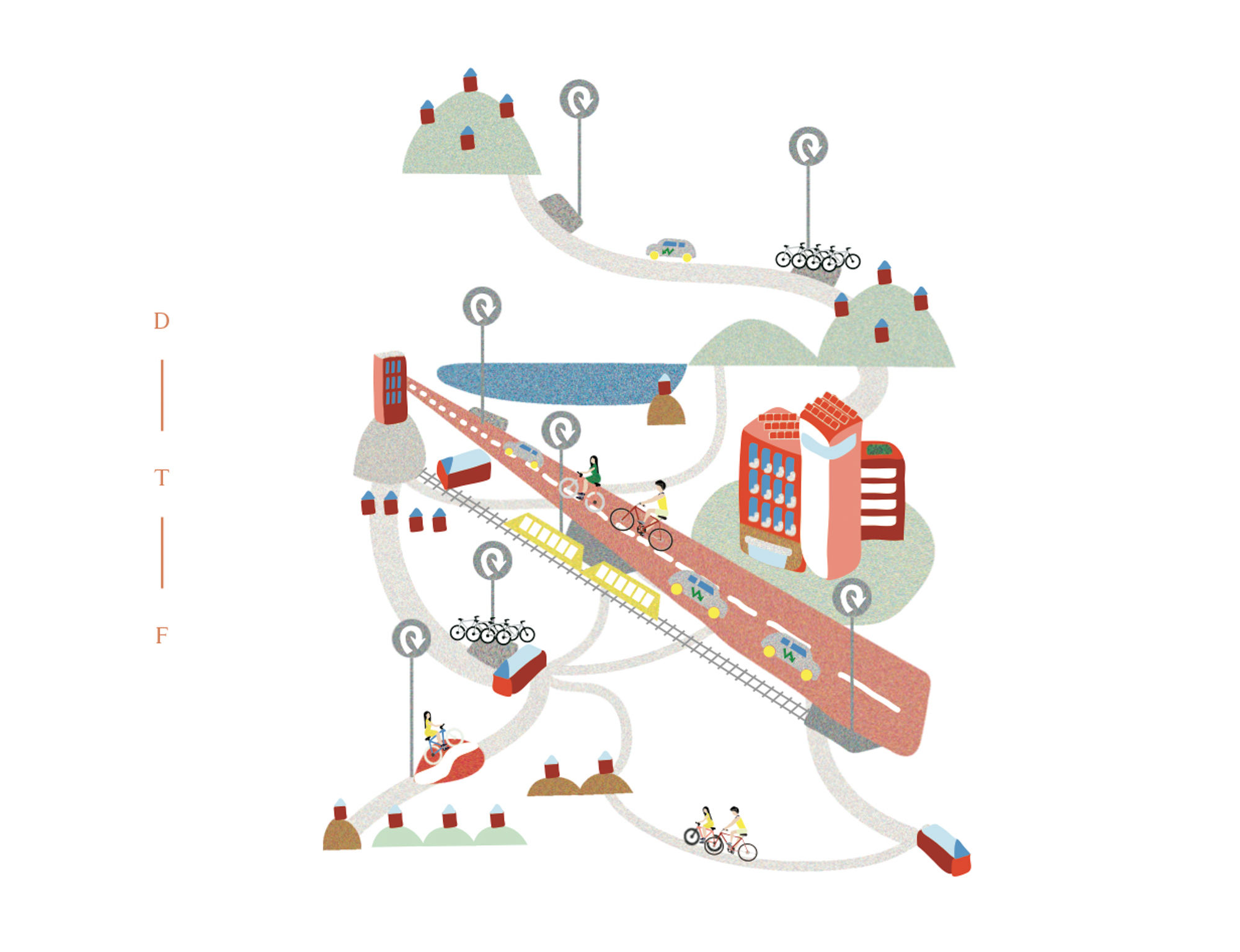

6. Less infrastructure, improved mobility

Traffic is at a standstill. Mobility is one of the greatest challenges in our highly ‘networked’ region. First and foremost, it is important to reflect on more compact development, and to limit travelling and transport distances. However, in terms of mobility, diverse revolutions are also imminent that have a radical and direct impact on the organisation of our living environment. Examples include technological innovation that can be used to achieve more sustainable mobility, the increasing automation of vehicles, or the rapid emergence of shared bikes and cars.

How could these developments be seized as opportunities to rethink the transport network in our region in a more integrated manner? How could we break the vicious circle of ever more roads and cars? How could we achieve better organised mobility through smarter use of our space and infrastructure? Recently, relevant research by design has been conducted from diverse perspectives. By bringing this knowledge and the diverse parties involved together, we hope to implement specific actions and initiatives in practice more quickly.

7. Ambitious open space

Open space and urbanisation are often viewed as two opposing forces. However, in a region where the city and the landscape are so closely interwoven, the mutual exchange between the open space and the urbanised area offers many opportunities. For example, this insight has grown significantly in recent years thanks to the use of research by design. Diverse initiatives have also been undertaken to bring together diverse parties that are concerned about the open space: managers of administrations, policy-makers, civic society, interest organisations, researchers and new actors. It is now a shared ambition to use the open space as a crucial building block and lever for future urbanisation in our region.

How could we take a more ambitious approach to the open space? Which conditions could be created to make room for productive landscapes? How could the open space be a place for food production, energy generation, leisure and nature? How could the open space optimally contribute or be self-steering with regard to urban development? These questions, the corresponding answers and initial experiences in the field form the starting point for collective reflection and knowledge exchange. The aim is to devise a fine-tuned agenda to develop more ambitious open space in the future.

During this session the focus lies on the water issue. The water issue not only affects a highly diverse range of other social, spatial, ecological and economic challenges at play in the open space. In addition, inspiring water-related methodologies have recently been developed in the Netherlands as well as Belgium, which by extension are also relevant to visions concerning the practical implementation of the approach to the open space.